Your credit score is a three-digit number that wields extraordinary power over your financial life, influencing everything from loan approvals and interest rates to rental applications and even employment opportunities. This numerical representation of your creditworthiness distills years of financial behavior into a single score that lenders, landlords, insurers, and others use to assess risk when doing business with you. Despite its profound impact on financial opportunities and costs, many people remain unclear about what credit scores actually measure, how they’re calculated, and most importantly, how to build and maintain scores that unlock favorable terms rather than create barriers to financial progress.

- Understanding Credit Scores: What the Numbers Really Mean

- The Five Factors That Determine Your Credit Score

- Why Credit Scores Matter: The Real-World Impact

- Building Credit From Scratch: Starting Your Credit Journey

- Improving and Maintaining Excellent Credit Scores

- Common Credit Score Myths and Misconceptions

Understanding Credit Scores: What the Numbers Really Mean

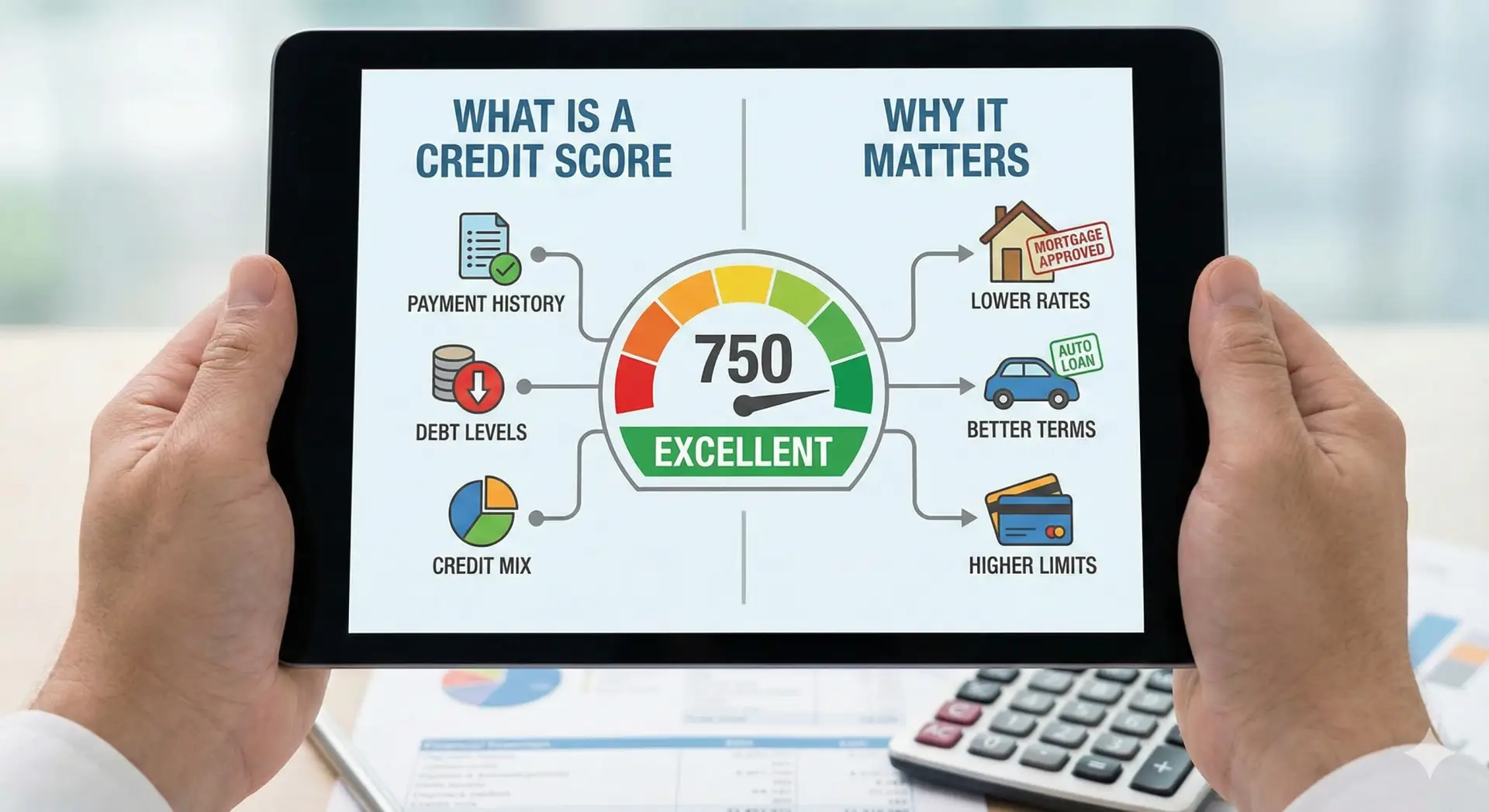

Credit scores typically range from 300 to 850, with higher numbers indicating lower risk to lenders. The most widely used scoring model, FICO, categorizes scores into ranges: Poor (300-579), Fair (580-669), Good (670-739), Very Good (740-799), and Exceptional (800-850). A competing model, VantageScore, uses similar ranges with slightly different thresholds. These scores predict the likelihood you’ll repay borrowed money based on your past credit behavior.

Lenders view scores above 700 as generally reliable, while scores below 600 signal elevated risk requiring higher interest rates or outright denial. The difference between score ranges translates directly into real money—a borrower with a 760 score might qualify for a 6.0% mortgage rate, while someone with a 620 score faces 7.5% or higher on the same loan, costing tens of thousands of extra dollars over the loan’s lifetime through compound interest.

The Five Factors That Determine Your Credit Score

Credit scoring models analyze five primary factors from your credit reports, each weighted differently. Payment history carries the most weight at 35% of your score, reflecting whether you’ve paid past credit accounts on time. A single 30-day late payment can drop your score 50-100 points, while consistent on-time payments gradually build strong scores. This factor answers the fundamental question lenders care about most: do you reliably pay your obligations?

Your credit score isn’t a judgment of your character—it’s a mathematical prediction of financial behavior. Understanding that distinction empowers you to improve the inputs that generate the output.Suze Orman, Personal Finance Expert and Author

Credit utilization comprises 30% of your score, measuring how much of your available credit you’re using. Keeping balances below 30% of limits on revolving accounts like credit cards demonstrates responsible credit management, while maxing out cards signals financial stress. Length of credit history accounts for 15%, favoring those with longer track records. Credit mix (10%) considers the variety of account types you manage—installment loans, revolving credit, mortgages. Finally, new credit inquiries make up 10%, with multiple applications in short periods suggesting increased risk or potential financial difficulty.

Why Credit Scores Matter: The Real-World Impact

Credit scores function as financial gatekeepers, determining access to opportunities and the cost of that access. When applying for mortgages, auto loans, credit cards, or personal loans, your score directly influences approval odds and interest rates offered. The financial impact grows with loan size and duration—on a $300,000 thirty-year mortgage, a 100-point score difference can mean $50,000 or more in additional interest payments.

- Landlords check credit scores to evaluate rental applications, with low scores resulting in denials or requiring larger security deposits

- Insurance companies in many states use credit-based insurance scores to set premiums for auto and homeowners policies

- Utility companies may require deposits from consumers with poor credit before establishing service accounts

- Employers in certain industries conduct credit checks during hiring processes, particularly for positions involving financial responsibility

- Cell phone providers often require deposits or deny service contracts to applicants with low credit scores

- Better credit scores provide negotiating leverage for lowering interest rates on existing accounts through balance transfers or refinancing

Building Credit From Scratch: Starting Your Credit Journey

Establishing credit creates a chicken-and-egg problem—you need credit history to get credit, but you can’t build history without getting credit first. Secured credit cards offer the most accessible entry point, requiring a cash deposit that becomes your credit limit while functioning like regular credit cards. Using these responsibly by making small purchases and paying balances in full each month builds positive payment history without accumulating debt.

Becoming an authorized user on someone else’s established account allows their positive payment history to appear on your credit report, potentially boosting your score without requiring you to use the card. Credit-builder loans, offered by some credit unions and online lenders, hold borrowed funds in an account while you make payments, releasing the money once the loan is paid. Student credit cards and retail store cards typically have lower approval thresholds, though higher interest rates make paying balances in full essential to avoid expensive debt accumulation.

Improving and Maintaining Excellent Credit Scores

Transforming poor or fair credit into excellent scores requires consistent positive behavior over time, but the payoff justifies the discipline. Pay every bill on time, every time—set up automatic payments or calendar reminders to eliminate missed payments. Keep credit card balances below 30% of limits, ideally below 10% for optimal scoring. If carrying balances, make payments twice monthly to keep reported utilization low even if you use cards heavily.

Avoid closing old credit cards even if unused, as this reduces your total available credit (increasing utilization) and potentially shortens your average account age. When shopping for loans, submit applications within a 14-45 day window—credit scoring models count multiple inquiries for the same type of loan as a single inquiry when grouped closely. Request credit limit increases on existing cards to improve utilization ratios without changing spending. Regularly review credit reports from all three bureaus through the official free annual credit report service to catch and dispute errors that might be dragging down your score.

Credit Score Recovery Timeline

Recovering from credit damage takes time, but understanding the timeline helps maintain realistic expectations. Late payments remain on reports for seven years but impact scores less as they age. Collection accounts and most negative marks also fall off after seven years. Bankruptcies persist for 7-10 years depending on type. However, the impact diminishes significantly over time—with consistent positive behavior, you can rebuild from poor to good credit within 12-24 months, and reach excellent scores within 3-5 years even after serious financial setbacks. Progress accelerates as positive history accumulates and negative items age.

Common Credit Score Myths and Misconceptions

Numerous myths about credit scores lead people astray from optimal strategies. Checking your own credit score does not hurt it—only hard inquiries from lenders applying for credit affect scores, while personal checks are soft inquiries with no impact. Carrying a balance on credit cards does not improve scores; in fact, paying in full each month optimizes both your score and your wallet by avoiding unnecessary interest charges.

Income and employment history do not directly factor into credit scores, though they matter for loan applications separately. Closing accounts after paying them off can actually harm your score by reducing available credit and account age. Paying off collections doesn’t immediately remove them from reports or restore your score, though recent scoring models weigh paid collections less heavily than unpaid ones. Understanding what actually influences scores versus pervasive myths enables strategic credit management based on facts rather than folklore.

Your credit score represents one of your most valuable financial assets, yet it’s entirely within your control to build and maintain. Unlike income, which depends partly on external factors, credit scores respond predictably to your behavior and decisions. Whether you’re establishing credit for the first time, recovering from past mistakes, or maintaining excellent scores, the principles remain consistent: pay on time, use credit responsibly, maintain low balances, avoid unnecessary applications, and give time for positive history to accumulate. The financial rewards of excellent credit—lower interest rates, better loan terms, easier approvals, and reduced insurance costs—compound over a lifetime, saving hundreds of thousands of dollars while opening doors to opportunities that remain closed to those with poor scores.